The Right to Art: fandom, parasociality, and the big thief of it all

quick thoughts on the modern artist/fan relationship paradigm

Every eight weeks or so, I drive down to Harbor City to get my highlights touched up by a woman I trust more than most people who come to my working memory. The drive is around an hour — more if I go during an inconvenient time for traffic which, in Los Angeles county, is a period that makes up most of the day. My hairstylist painted my naturally espresso brown hair into a platinum blonde for years until, with a tone both stern and loving, she looked at me through the mirror and said “there’s a lot of breakage here.” And I knew she was serious.

Life as a platinum blonde is exactly as fun as they say it is. I’ve never gotten more matches on dating apps, up-and-downs on the street, and numbers scrawled on cocktail napkins before or since. As a young woman with a strong desire to feel both irresistible and exceptional, the fact that Martha Vidales has convinced me that acquiescing to honey blonde highlights is The Way for me is nothing short of a miracle.

The contract between me and Martha is this: I book an appointment with her, she does my hair to my liking, I pay her for her time and skill, and then I leave — circuit complete, case closed. Because I am her client, I decide on the Vision for my hair and she executes it (perfectly, every time by the way). Sometimes a bang looks out of place or I figure we could go a little bit longer with the toner, and she adjusts to meet my standard. She is using her skills to execute my Vision, which has been the contract between hairstylists and clients since the beginning of time.

This is a perfectly appropriate contract for people who are buying or selling a service. If you hire someone to mount your television, you get to tell them how high — even if you miscalculate and doom your movie night guests to leave clutching their necks. In situations such as these, the Vision of the client prevails above all. The customer is always right, even when they’re wrong. The guy who mounted my television doesn’t give a shit that I didn’t know what I was doing when I suggested, yes, that high. He’s the expert, but I’m paying, and he gets paid either way.

There is no such contract between musicians and fans.

There are a number of ways in which fans are legitimately entitled to things from artists. If you buy a song for $0.99 on iTunes, you should expect to see it in your digital library. If you buy tickets for a concert, you should expect to show up to the venue and see the artist perform. But what happens when the song you bought isn’t the version you wanted? Or when a live performance doesn’t sound like the record? Are you owed something? Is the artist indebted to you? Some fans seem to think so.

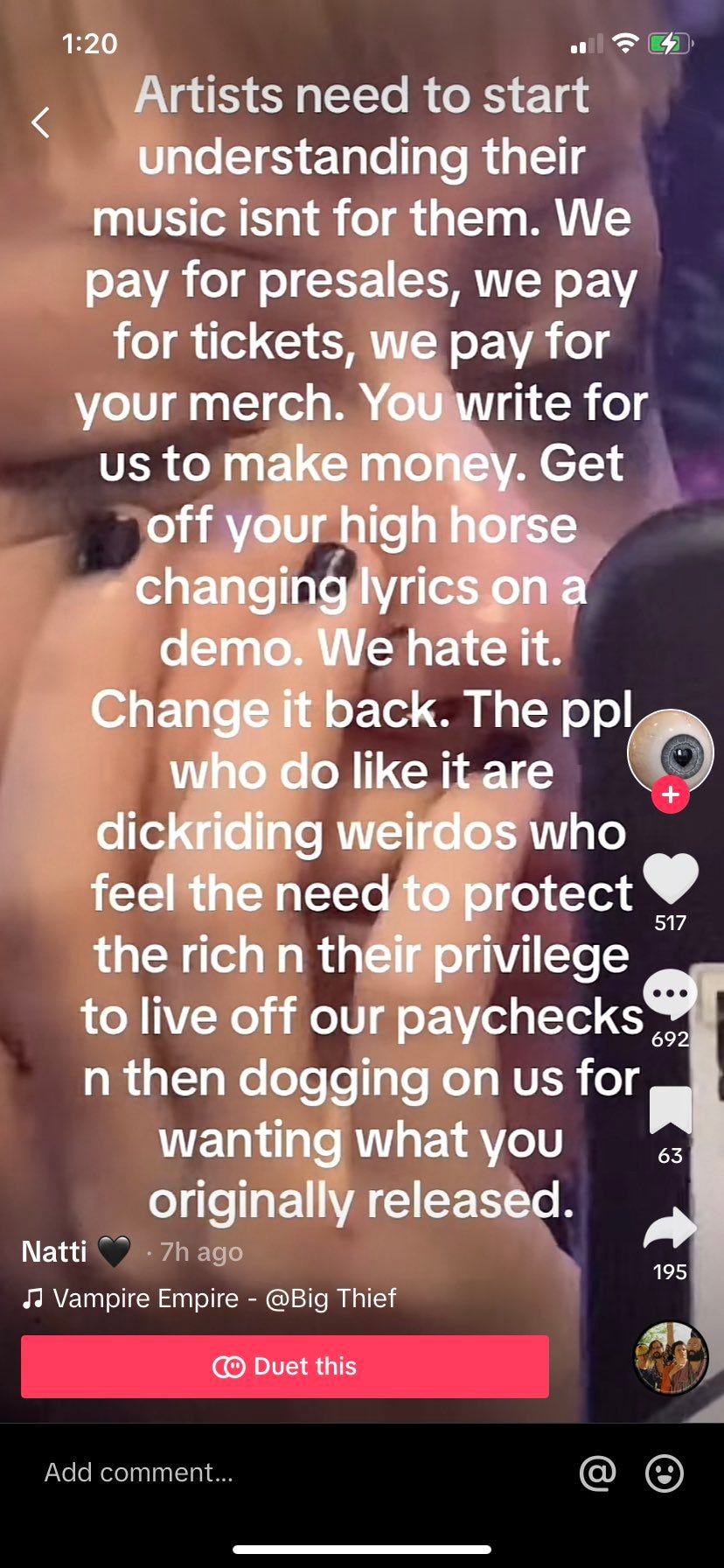

This is a screenshot of a TikTok which was posted as a Tweet, which was subsequently screenshotted and reposted to the Stereogum Instagram account, where I eventually came across it. This line of digital upchuck tells me one important thing: what I’m seeing is a hot take. I can tell by the like:comment ratio in the original TikTok alone. I won’t continue this essay with the chiding “you kids are chronically online” rebuff that falsely establishes this sentiment as a generational norm of thinking — a practice both cheap and reminiscent of when Fox News attempted to sincerely warn that the kids were eating “NyQuil chicken” and passing out fentanyl candy on Halloween.

This poster is responding to the release of the song “Vampire Empire” by Big Thief and, specifically, the differences between the recorded version and the one that was played live on The Colbert Show earlier this year. The block of text, while not wholly representative of the opinions of most young fans, is the logical conclusion towards which many are on their way.

For fun, why don’t we flesh out the artist/fan contract proposed by this user a little more. Succinctly described in the the third sentence, it is this: “You write for us to make money.”

In this world, the fan is the employer of the artist. The artist at work should, like a hairstylist or a handyman, be oriented towards the goal of pleasing the customer. When the artist sits down at the piano to write a song, they should think not of their own personal experience which they intent to transmit into music but of the experience a fan might have when listening. An album, then, may be a manifest of the collective desire of the fans. The musician is the mouthpiece for the Vision of the fans, and doing the job well means doing it satisfactorily to the preferences of, supposedly, the highest percentage of the fanbase who can manage to artistically agree.

This contract certainly works in the favor of apps like TikTok, which can tell you with a high accuracy which songs will perform the best. Big Thief may find greater success in the future, according to this user, by posting demos to the platform and compiling an album of the most “liked” tracks. That way, the majority of the fans get exactly what they want, and we’d never be forced to listen to the mind-blowingly good recorded version of “Vampire Empire” ever again. In case you haven’t picked up on it by now, I would consider that to be a very bad and depressing idea.

Also, you don’t employ your favorite artist.

For most high-profile, signed musicians (against which this kind of critique is levied almost exclusively), the money that fans pay for records or tickets or merchandise does not go directly from the sweaty-palmed teenager into the bank account of the band. In fact, your favorite band may still not be seeing a cent from their most popular release due to increasingly predatory contracts between artists and labels. I personally have an incredibly fair contract with my label that I am happy with. And I signed it knowing full well that I may never make a single dollar from a streaming service because of it.

When you see the opening act at an indie venue mention that they’ll be selling t-shirts or tote bags or stickers at the merch stand, you’re witnessing a cry for help. For small artists, merchandise sales at shows are essentially the only way to make money “through music.” When I’ve been out on the road as an opener for mid-sized indie bands, my nightly rate was the industry standard of $250 — a profit that my travel expenses alone ate up immediately. Touring is extremely expensive, especially if you have a band, complicated equipment, or visual effects. Even established artists with millions of streams who are signed to major labels (yes, the “rich n privileged” who are living off of your paycheck!) struggle to make ends meet on the road. Just last year, rapper Lil Simz canceled her full U.S. tour because she couldn’t afford to play the dates.

While larger acts of course have more security within these matters, the fact is that musicians do not have one single employer and most musicians make their money from other related but indirect avenues. Artists have their own contracts with merch distributors that involve cuts to the distributor themselves, venues, affiliated companies, and labels. Even indie artists are partnering with the big corporate guys to schill Crocs and Sprite and anything else that will support the financial longevity of their project (the Indigo De Souza Converse rock by the way). The whole web of moneymaking as it relates to music is an ever-confounding one that relies, increasingly, on other industries to support it.

Almost no one, at this stage of the music industry, makes money “from music” alone.

But my interest in this TikTok user’s sentiment goes far beyond a misunderstanding of the logistics of the industry — logistics I didn’t understand myself until experience required it, and the nuances of which I don’t expect casual fans to know. I am more interested in the conceptualization of artist/fan relationships and, in particular, how social media is changing that landscape.

About a week ago, Doja Cat posted a Thread (Threaded? Weaved?) in which she cut through any illusion of a personal relationship to her fans like a hot knife through butter. Watching from the sidelines of a PopCrave screenshot, my first thought was “is she trying to kill her career?” My second thought was “wow, she’s getting off the train.”

I don’t think any modern musician has quite cracked the code on parasocial fan relationships. It seems as though the train to reachable relatability — the way to fans’ hearts that most artists board one way or another — is threatening to arrive at its destination. We’re at a tipping point where artists are deciding either to ride it to the end or jump off into the tracks.

Taylor Swift is firmly on the train, digging in the parasocial bestie mine since the dawn of her career — she invites fans to secret sessions, sends personalized merchandise, and has created a culture of friendship bracelets at her shows. If you meet her on the street and tell her you love her, I have no doubt that she will look earnestly into your eyes and tell you that she loves you too.

One of my favorite social media follows and prolific artist, Azalea Banks, jumped long ago. She has a masterful command over her fans, having called them any number of slurs and derogatory terms, hurling insults at their tastes, and replying crassly to any number of kind, well-meaning comments. She has surpassed the threshold of cancellable offenses and exists now as a dark mother to anyone brave enough to keep stanning. Her fans are like hit dogs who keep coming back, and they love to do it! That’s the charm! Banks is no-bullshit. She is not your bestie and she makes sure that you know it.

Banks is at the outermost edge of a very unpopular extreme and succeeds only because she is so radical in her approach. Most artists stray from commenting on their relationships with fans altogether save for positive platitudes like “I love you guys” or “I’m so grateful.” Artists who have attempted to find a middle ground end up in controversy and most, it seems, eventually capitulate to embracing their fans as friends. To succeed and be beloved, the modern artist must go along with the ruse that not only are they personally connected to each and every fan, but that they like it that way.

It is doing a service to no one to keep this conversation unspoken. Artists deserve to have healthier relationships with their fanbases — ones that exist outside of the binary of bestie or adversary — and fans deserve the experience of relating directly to an artist’s work rather than their own projection of someone who will exploit their attachment for money.

The artists I find most compelling are those who continually take risks, surprise people, and experiment stylistically. When fans feel that they are enmeshed with a performer in such a severe way — a way that gives them license to control the music — they are fundamentally misunderstanding the role of the artist. If these people got what they wanted, they wouldn’t be happy with it.

A mob-sized conglomerate of fans, if put to a vote, would never think to tell Caroline Polacheck to use her awe-inspiring voice in place of guitar solos in her music, a feat both unconventional and highly weird on first listen that has since become a staple of her artistry. The sacred concept of a “deep cut” would fade into extinction. You could no longer feel the magic of stumbling upon an underground indie band with a grating, special sound. When fans become board members who feel that they’ve bought stock in artists, artists lose their magic. Not to be all “art comforts the disturbed and disturbs the comfortable,” but truly I shudder to think of a world where people are dissuaded from making genuinely weird, off-center, impolite creations. That is a world which, to me, is circular and boring, overly pedantic and without an engine with which one could be encouraged to search for meaning.

The stuck place we find ourselves in circles back to the idea of ownership and debt — what is owed and by whom? I think this is the wrong frame to have for this conversation. Unless you have hired someone to play a song or produce a painting or write a poem specifically for you, art is not owed to anyone. Many people have listened to a song and had this thought: “hm, I would have done something different here.” This is how most artists begin their craft, using previous work as a foundation to establish themselves and their vision. There is a great beauty in this conceptual collaboration — the new artist seeks not to change the original material, but to use it as a tool to reflect on themselves and how they might like to create in the future. The answer is not and will never be “this is how I like it, and therefore the original work should change.”

This is not a diatribe against art criticism — it’s exactly the opposite. Hate the recorded version of “Vampire Empire?” That’s an excellent place to start when thinking about writing your own song. What would you change? How did the live version capture the essence of the song better, in your opinion? What could you take from this comparison to implement into your own work?

We have lost strength, culturally, in the creative muscle. We focus on if art is meaningful to us directly, if it’s up to our particular standards, and if it’s not, we seek to find fault either in the work or with ourselves. We’re moving towards a future of perfectly polished Artificial Intelligence music and playlists that are curated just for your ears so that one day, you may never have to hear a song that puzzles you ever again. What a bleak future that is.

Listen to a band from your least favorite genre. Go to a house show where you don’t know anyone and the floor is sticky with beer. Listen to your favorite artist’s “worst” album a few times, all the way through. Resist the urge to control, to attach, to judge on a value scale. And then listen to the recorded version of “Vampire Empire,” cause that shit rules.

love this eliza!! its crazy how the people nit picking vampire empire are quite literally, as the lyric in the song goes, "spinning them all around and asking them not to spin" !! big thief is an artist and it is THEIR art!!! tbh i love the studio version more, i love how emotional it is!

the way you write is so lucid and precise. capricorn excellence ugh.