In March of last year, after a sold-out show at Baby’s All Right in Williamsburg, I was approached by 30-40 fans at once as I was loading merch up into the van. I was overwhelmed and exhausted, but also overwhelmed with gratitude. I wanted to say hi to everyone individually, but found it impossible. I spent time with that group as much as I could, and when another was coming up on the horizon, my manager put his arm around me and said “let’s go across the street where you’re not famous anymore.”

This is the kind of famous I am. I am “cross the street” famous. If I am somewhere where people who like my work are present, I have the potential to be mobbed like a pop star. And if I cross the street, nobody at all will recognize me. To me, it is the perfect balance. I am recognized about twice a week in Brooklyn. The way I actually, physically live my life is almost not at all impeded by being sort of famous. People are generally kind to me. I mercifully do not have any stalkers. And yet.

Being sort of famous has totally changed the way that I think about everything. It was not something I was prepared for. Over the course of the last three years, I’ve had several nervous breakdowns specifically about my relationship to my audience and their relationship to me. I am one of the more outgoing, social people I know. I am a classic extrovert. I love to share. And there was nothing I could do to prepare me for how even modest visibility would change my brain.

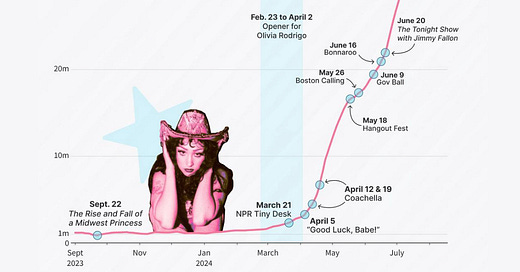

So, I think of Chappell Roan. Chappell Roan, who was on TikTok with the rest of us in 2020, after having just been dropped from her label after the release of “Pink Pony Club.” I think of how fucking crazy even a modicum of fame has made me feel, and I think of this graph, which gives me nausea:

In the words of prescient Tweeter and fellow substacker

, “if I became as famous as Chappell Roan as quickly as she did I would become the joker within, like 2 days.”Yesterday, Roan published two videos addressing her fans and their behavior. She sets up a hypothetical: if you were to see a “random lady” on the street, would you yell at her from a car? Harass her online? Doxx her family? No, Chappell! We scream. I am very normal and would never say or do those things to you or anyone. I can’t believe those horrible, entitled people, we say. Then she asks us: Would you ask her for a photo? Would you ask for her time? And we think about Chappell Roan, more of a stained-glass Mary Magdalene than a “random lady” to us. And say… maybe I would?

It’s easy to say that stalking, harassment, and physical intimidation are things that anyone has the right to reject (except in the case of a few particularly virulent quote tweeters who believe that absolutely any abuse faced by a famous person is simply “part of the job”). But what about the more innocuous “fan behavior?” Surely, just saying hello on the street or asking for a photo should be allowed and indeed is “part of the job?”

Earlier this year, I played a sold-out show in Chicago. The energy was amazing, and I came off stage feeling wiped-out and proud of myself. Then I realized that the stage door had closed behind me and the venue side-door in front of me was locked. The crowd of hundreds came streaming outside, surrounding me. I turned to look inside at the venue, and people were there too, pressing their phone cameras up against the glass. I huddled closer to my band and tried to wave as the mass of people around me grew. Through my earplugs, I could hardly hear anything at all. I just tried to keep smiling until a security guard let me back into the venue, my heart racing fast enough to hear it in my temples.

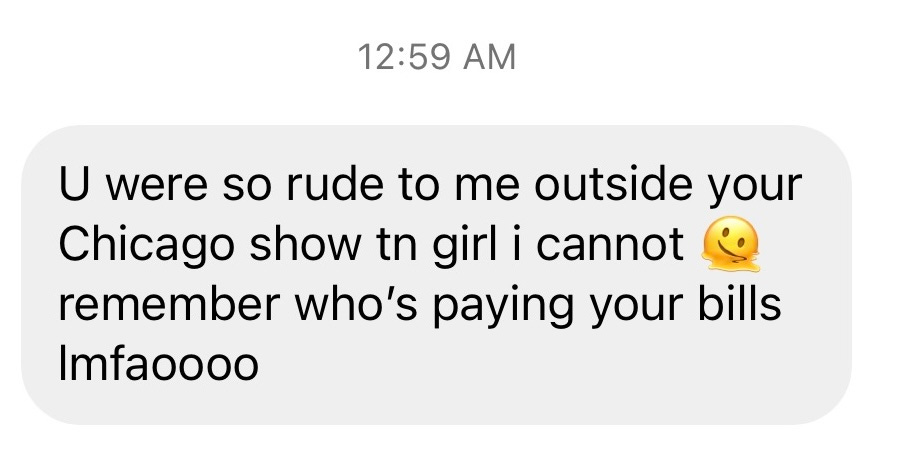

Later that night, I got a DM request from an account I do not follow:

This is a message from a fan, who ostensibly engaged in the normal “fan behavior” of (I’m guessing here, as I was not able to identify or hear anyone in particular) asking me for a photo or trying to engage me in conversation. This message made me want to go Joker mode. It made me want to delete every account that I have, never put anything on the internet ever again, and tattoo “I AM NOT YOUR FRIEND OR YOUR EMPLOYEE” across my forehead. I obviously did not do that, but a similar impulse hits me, genuinely, about once a month.

I suspect that Roan’s resistance to public fan interactions are about more than the inconvenience on her time. There is something obviously wrong with direct harassment and threats. But there is also something that feels inherently creepy about people feeling entitled to, not just the character you reproduce for their consumption, but the person you are. And maybe that is what the job of being famous entails now, but it is eerie.

I’m thinking of the Mark Fisher definition here, where he describes eeriness as a “failure of absence” or a “failure of presence;” either something present when there should be nothing, or nothing present when there should be something.

This is how I feel about having an audience. I am both overly present and overly absent; I am everywhere, inundating the audience with content and yet cannot promise them genuine access to me as a person. It goes the same way with the audience, who is perpetually engaging with the version of myself I reproduce for the internet, but not my true, authentic self. Nobody is quite touching. It is everywhere and nowhere.

During one of my nervous breakdowns, I thrashed about in several interviews, insisting that anything you see of me online is NOT REAL and is the responsibility of YOUR PROJECTIONS ALONE. I was in a thick period of extreme dissociation and isolation. I hardly felt real and spent long hours convincing myself that I could not in actuality feel the microscopic space that existed between the atoms of everything. That I could still touch things and be a part of the world. I wanted to communicate that I still belonged to myself, that I cannot ever belong to the audience, that in fact nothing genuine about me could ever even be touched by that faceless, growing mass of people. This is, of course, not true. If you interact with my work, you can probably get a decent sense of who I am as a person. This fact is deeply terrifying to me.

I see this kind of frenetic energy in Roan’s videos. It’s not just “the picture” or “the hello;” it’s the convergence of online admiration and real-world interaction. It’s the all-consuming knowledge that people are consuming you. Any person in their right mind, when being devoured, would scream out: CAN SOMEBODY COME TAME THIS LION?

An interesting parallel for Roan’s video was a video of Taylor Swift, looking to be about nineteen or twenty, talking about fame. She bemoans celebrities who complain about how difficult it is to be famous, how irritating fans are for wanting photos or access to their time. As the perfect Americana country-pop starlet of the 2010’s, her modus operandi was, above all, that she was grateful. That, in fact, she found it fun and entertaining that men broke their necks on the freeway to take a video of her driving around. That she would never for a moment complain about what is, on most every account, a pretty perfect life. And then she went on to write several albums about how absolutely devastating it is to be a person that everyone wants to take a photo with.

I am glad that our pop stars of today feel comfortable speaking to their audience the way their audience speaks to them. I hope we are at some sort of tipping point — one where we can interrogate our roles are consumers and creators. I hope that someone out there is making sure that Chappell Roan is getting good sleep and taking time to talk with her friends in the real world and not totally fall into the rabbit hole of online speculation. I hope that we are all asking ourselves to be honest about how we interact with the artists whose work we respect. I hope that we can all stop taking photos of celebrities at the f#$cking airport, universally known as the worst place to be and therefore the worst place to be seen. I hope you liked this essay. I hope you like me.

Excellent piece! As a fan, I think the desire to ask for photos and take up a celebrity’s time is directly in response to the eeriness Eliza describes. When I’m engaging with art (or content) I feel that parasocial connection and the absence of real connection. I think that asking for a celebrity’s time and for a photo is sort of a desperate attempt to bridge this eerie gap. The desire for human connection is very real, and yet in the case of celebrity totally fantastical. I think that fans (myself included) need to interrogate what it is they’re looking for when they’re seeking acknowledgement, and if a photo or a quick conversation will actually get them closer to achieving it.

The proliferation of Stan culture goes hand in hand with the immense loneliness young people are feeling. One of the things I’ve always appreciated about The Pod is how you insist that we don’t fucking know you girl!!! Acknowledging the media I consume is a close approximation for meeting a social need helped me identify what it is I envy about the dynamics I see online. This insight ultimately led me to seek that out in the real world, which has been far more fulfilling because it’s my beautiful fucking life to live. Reverence in our culture is a sign of desperation. The surface level dismissal of “it’s not that big of a deal to ask for a photo!! This artist must hate their fans” conveniently protects the fanatic entitlement to surveil people in the public eye. Instead of building a safe image of someone based on every piece of information I can glean from online, I’m more inclined to turn towards my friends and become obsessed with how they might be the next Chappell.